Gustavus students marched in the nation’s capitol last week as part of a nation-wide student-led protest against the Keystone XL pipeline. Demonstrating under the name XL Dissent, 25 Gustavus students joined over 1,000 other youth from across the United States in the largest act of youth civil disobedience in a decade.

Gustavus students represented the largest collective group of youth protesters from the state. With 70 youth in attendance overall, Minnesota had the second-largest state representation at the protest, coming in behind Massachusetts.

According to student reports, after marching, the protesters fastened themselves to the White House fence with plastic zip ties and staged a mock oil spill on the sidewalk outside.

After repeated warnings, police arrested demonstrators for blocking passage of sidewalks. Nearly 400 students were arrested, including eight from Gustavus.

The arrests have raised some eyebrows among students on campus. Some viewed the arrests as contrived and questioned the need for orchestrating them.

Senior Political Science Major Anna McDevitt, one of the key Gustavus organizers for XL Dissent, spoke to the mechanics behind the notion of risking arrest. For her, risking arrest is a key component of effective civil disobedience.

“Throughout history, civil disobedience has played a huge role in shaping our nation’s history—and our world’s history—and much of it has been student-led. Our protesting Keystone XL is our generation’s way of being a part of that tradition of civil disobedience. Our willingness to be arrested is our way of saying, ‘we’re not afraid, we’re willing to put ourselves on the line to show what is important to us,’” McDevitt said.

Though an important statement, other students saw the arrests as a reminder of their privileged position in society. Senior Political Science and Scandinavian Studies Major Annalise Dobbelstein, one of those arrested, voiced her inner conflict.

“I was definitely conflicted about getting arrested. I mean, I raised my own bail money and had a plan to get out of jail once I got in. I had the privilege of getting arrested and knowing that it wouldn’t make a huge mark on my future, unlike so many who are wrongfully arrested and never get out of the [jail] system. I still grapple with that,” Dobbelstein said.

First-year Leigh Todd, who provided jail support for those arrested, said that from a practical standpoint, risking arrest was a way of drawing more attention to the protest by allowing them to spend more time on the streets and in the public eye.

“The arrests were a very public way of showing people what we believe in. If we had just marched the streets, it would have just been seen as ‘just another march,’ and we wanted to spend as much time on the street as possible. The arrests allowed us to do that—to gain people’s attention and also the president’s attention,” Todd said.

Motives for Protest

For those who protested, getting President Obama’s attention was key, considering that the final approval for the pipeline’s completion lies in his hands.

For many, the president’s decision serves as a test of his commitment to environmental issues. Many Gustavus protesters considered their involvement as holding the president—who many of them helped vote into office—accountable for past promises.

“For a lot of us, the first president we voted for was Obama because he said he was going to be a climate leader, not a pipeline president. He campaigned as a climate champion and we were excited about that. This protest is us holding him accountable [for the commitment he made]. We were the young voters who elected him, and we want to see him make the right choice,” McDevitt said.

Dobbelstein echoed the political motivations behind her involvement in the protest and added a note of urgency to the impending decision.

“He [the president] has one time to make this decision. I voted him into office twice and I am not okay having [the Keystone XL pipeline] potentially go on my record and not having done anything to stop it,” Dobbelstein said.

For other students like Todd, the pipeline would literally hit them where they live. Todd’s hometown is York, Nebraska, one of the many communities that would be directly impacted by the construction of the pipeline.

Todd raised two major issues posed by the pipeline: its potential to drastically compromise the Ogallala Aquifer, a major water source in the region, and the irreparable damage the pipeline poses to farmland.

“If the pipeline were to ever leak, it would really affect my community. [My county] is mostly corn and soybean fields, farmland, and unstable country roads. If there were a leak, not only would it tamper with the Ogallala Aquifer, it would tamper with farmer’s fields by passing directly through them. Those fields represent a lot of work, and [the pipeline] would destroy that,” Todd said.

Despite the deep commitment to the issue, the forecasts regarding Obama’s final decision were mixed.

“I honestly thought [the president] was going to approve the pipeline. So, for a lot of us, [the protest] was our last chance to influence his decision. After this action, however, I feel there’s no way he can accept it. Seeing the media attention [the protest] got—with it being the largest youth civil disobedience act in a decade—I really think we sent a message,” McDevitt said.

Todd was less optimistic and said she has tried to avoid thinking about it because of the distress it causes her.

“Right now, I would say probably yes, [the president] will approve it. Money always wins. I haven’t thought about it though, because I don’t want to think about it. This issue really hits home—the pipeline would destroy everything back home for me,” Todd said.

Future Predictions and Plans

Despite mixed predictions of the president’s decision, the Gustavus protesters see their trip to the capitol as momentum for rallying future engagement on issues of environmental justice.

“I knew that once we got out there, it would be a huge motivator for us returning to campus. After our return, we all said, ‘okay, what are we going to do now?” McDevitt said.

Future initiatives include the Divest Gustavus campaign and halting the exploitation of tar sands in Minnesota.

McDevitt hopes to organize students this spring against the Alberta Clipper, a pipeline that comes through Northern MN, which is in the process of applying for a permit to expand the pipe to a capacity even larger than Keystone XL.

For those involved in the protest, these plans for future engagement represent what they see as a larger call to action for their generation.

“Each generation has its own challenges and each must address them. Our protest says to the world that, right now, climate change is the most threatening thing to our future—this is what our generation’s challenge is and we’re going to fight it. We want a livable future and we’re not going to let corporations make decisions for us,” McDevitt said.

Todd echoed the call for continued action.

“We’re not just going to protest, we’re going to take this further. We’re going to divest Gustavus, we’re going to keep creating awareness,” Todd said.

With less than 60 days of public comment left on the Keystone XL decision, student protesters encourage those who want to voice their opinion to write letters and contact their local state representatives.

Students wanting to get involved with future environmental justice campaigns like Divest Gustavus and the fight against tar sands should contact Divest Gustavus at divestgustavus@gustavus.edu.

What is Keystone XL?

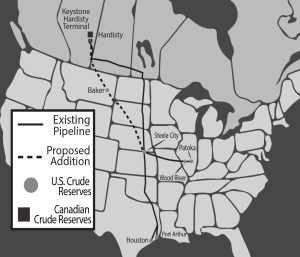

Keystone XL is a 1,179-mile pipeline that would carry crude oil from Canada’s tar sands, in the province of Alberta, across parts of eight states and over the vast Ogallala Aquifer, to US refineries in Nebraska, Illinois and the Gulf Coast of Texas. (See map to right for proposed route of Keystone XL and existing pipeline).

While operations in the southern leg of Keystone XL has already begun, plans for the northern section are on hold, pending presidential permit.