Politics – where language goes to die

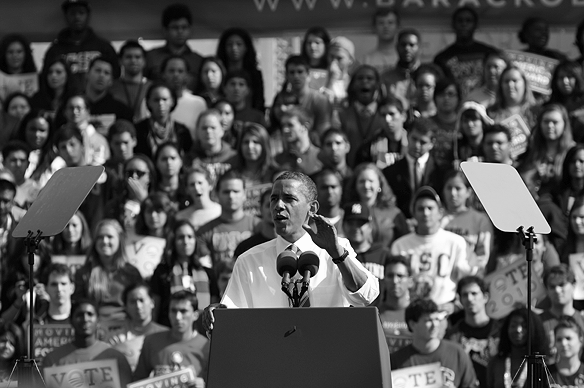

On the 2008 campaign trail, President Obama said, “Change will not come if we wait for some other person or some other time. We are the ones we’ve been waiting for. We are the change that we seek.” This seemingly progressive statement certainly has its merits. We’d like to think that we’re too insignificant to effect change and that the radical reformers of bygone ages had something we don’t—thereby absolving ourselves of significant responsibility. The individualism and humanism implied in Obama’s statement is quite valuable for encouraging real reform in the real world by real people—not icons in some far-off realm.

On the 2008 campaign trail, President Obama said, “Change will not come if we wait for some other person or some other time. We are the ones we’ve been waiting for. We are the change that we seek.” This seemingly progressive statement certainly has its merits. We’d like to think that we’re too insignificant to effect change and that the radical reformers of bygone ages had something we don’t—thereby absolving ourselves of significant responsibility. The individualism and humanism implied in Obama’s statement is quite valuable for encouraging real reform in the real world by real people—not icons in some far-off realm.

However, Obama’s statement was most certainly political in its vagueness—a deliberate move to inspire voters with populist appeal. His choice of words could include anything and everyone—glossing over innumerable individual differences for the purpose of uniting people behind his run for political office. His very vagueness significantly blunts the strengths mentioned above. When examined, there’s an element of exploitation to this type of political statement in that Obama is purporting to speak for everyone. However, the President is not me and is incapable of truly speaking for me. I’m not accusing Obama here, but his statement reveals that it’s all too easy for politicians to quietly slip divisive dogma and groupthink into unsuspecting minds under the guard of such populism. Language is malleable enough that tyranny can easily be disguised as freedom, tradition disguised as innovation, etc.

Simply call to mind an occasion of a politician making a statement about war. Ever heard the term “collateral damage?” It‘s unintended damage to innocent people and property as a result of a military offensive. Imagine the vastly different response politicians would get if they said, “Our missile destroyed the intended target, but also inadvertently killed or maimed thirty children in a nearby school.” People often don’t think about what lies behind the term “collateral damage” and are thereby led to believe that the actions of their government are ethically sound.

Consider also the famous statement made by former President George W. Bush: “Every nation, in every region, now has a decision to make. Either you are with us, or you are with the terrorists.” Thankfully, many saw the logical fallacy within this crass statement. As George Orwell put it, “Political language […] is designed to make lies sound truthful and murder respectable, and to give an appearance of solidity to pure wind.”

As a result of rhetorical vagueness in the political arena, public discourse has become a game of who can more strictly adhere to ideological dogma and social issues that are argued with the exchange of witty quips. This is not absolute, but our use of language is certainly affecting our political systems and our thought in general. The relationship between thought and language is a reciprocal one. Orwell wrote of this when he said our language “becomes ugly and inaccurate because our thoughts are foolish, but the slovenliness of our language makes it easier for us to have foolish thoughts.”

Combatting rhetorical vagueness is something we must all engage in if any lasting difference is to be made. Culture is created through the medium of language, and this very act is just what makes language so enormously powerful. The medium determines what can and cannot be said, what ideas can and cannot come to fruition, and where political power is manifested.

As the late Neil Postman told us, “our languages are our media. Our media are our metaphors. Our metaphors create the content of our culture.”

In other words, the stakes are high. Language is ubiquitous and changes imperceptibly. Preventing it from degrading into imprecision is a task requiring constant vigilance by nearly all members of a given culture. In a real, apolitical sense, “We [must be] the change that we seek.”

As Gustavus students, this is especially relevant in light of the political and social issues we readily participate in—both on campus and off. We must demand precise language from our leaders and hold them to standards of intellectual candor. We must express ourselves with precision worthy of the ideas behind our words. Ideas only grow and expand as far as language enables them to. Who creates language? We do.