Race, to the top

In the presidential election of 1960, Bobby Kennedy and his band of merry men orchestrated for his brother one of the closest victories in the history of American politics. This monumental feat was made all the more impressive because John F. Kennedy’s Catholicism, something we wouldn’t think of holding against a candidate today, was of serious concern in that era.

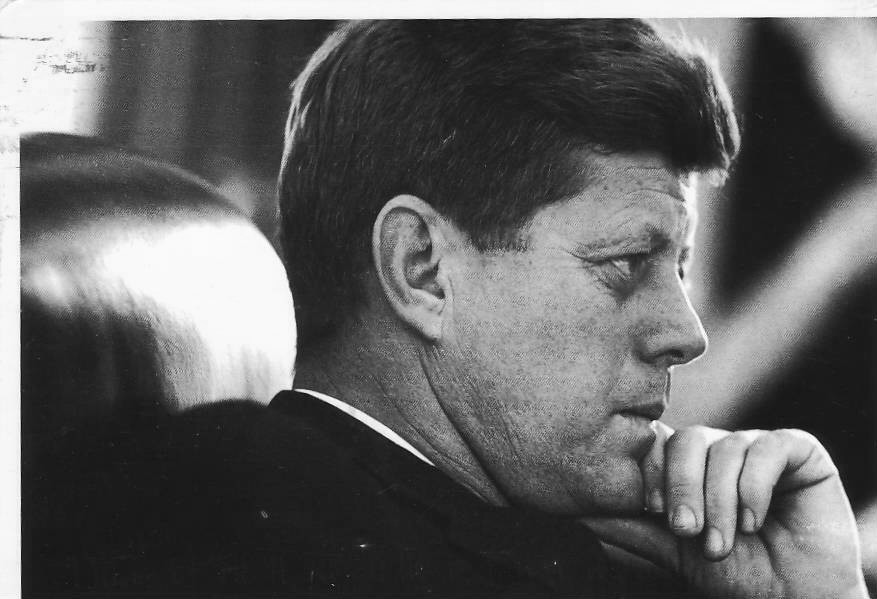

JFK was the product of an insanely privileged upbringing. Thanks in large part to his father’s ruthless business ventures, the Kennedys were among the wealthiest and best connected families in the country. He was tall, white and handsome. He went to the best schools, hobnobbed with royalty and dignitaries as the son of the Ambassador to the United Kingdom at the Court of St. James’, and because of this upbringing possessed formidable charm and intellect.

But for all his privilege (and I use that word intentionally), he and his family also knew what it was like to be scrutinized and to some extent discriminated against for something that they had little or no control over: their religion.

Indeed, his election played a significant role in dispelling unwarranted fears the country had about Catholics in positions of power. It may or may not have been that these experiences contributed to the Kennedy brothers’ strong advocacy of Civil Rights throughout the 1960s, but they were allies of that movement, nevertheless.

As the de facto heir to a colossal fortune and supremely powerful family, Jack Kennedy experienced the highest heights of what we now call white privilege, but still possessed empathy for the underprivileged, which helped him and his younger brother Bobby be strong advocates for the socially and economically downtrodden.

The concept of privilege as a societal phenomenon is one most Gusties are never exposed to, much less consider thoroughly in assessing successes and failures in their lives. This definitely, especially, includes myself.

Put simply, it is the idea that my status as an affluent, white, heterosexual male in American society awards me unspoken advantages in life that I may not even realize. I get to view myself as normal while “minorities” are the ones who are different.

To others I appear honest, hardworking, respectable and trustworthy, never having to earn their respect. Though it may or may not be true that I possess these qualities, others assume so because of my gender and because of my race, nothing more, and generally assume worse of non-whites and women.

Thus, I am unwittingly rewarded with opportunities I take for granted that others will never come close to, chalking my successes up to hard work while telling the less successful to simply work harder and opportunity will come.

Race and privilege remain as integral to American politics as they did in the 1960s, though perhaps not as visible. They will hopefully take center stage in our national dialogue as Republicans struggle to explain how they lost non-white voters and women by such huge margins in the 2012 election.

“The white establishment is now the minority,” bemoaned one commentator, upon realizing appeals to white males of means will no longer be enough to win national elections for his party. “The demographics are changing, it’s not a traditional America anymore.”

As JFK said in his Profiles in Courage: “A revolution is coming—a revolution which will be peaceful if we are wise enough; compassionate if we care enough; successful if we are fortunate enough—but a revolution which is coming whether we will it or not. We can affect its character; we cannot alter its inevitability.”

It’s been, quite literally, my privilege to write for you this year. A common tagline has been, “Think more, believe less.” It is a reflection of how the Gustavus experience has helped me change. Belief is often used as an excuse to ignore inconvenient information. Belief, in this sense, is the enemy of thought and reason, for it permits you to overlook unwelcome truths.

It was inconvenient for me to accept that I enjoy an undeserved elevated stature in society, but I am made better for it. I am not comfortable or confident in talking about these issues, and have surely offended my share of friends in the attempt. Nor am I likely to ever fully understand what it is to struggle daily against an unjust system as it has so clearly worked in my favor. But in that attempt to find understanding there can be progress for all of us. You need not be an activist on this front to make a difference. Seeing the problem plainly can, and will, change your perspective on life, and help us to all be allies in the continuing movement towards equality for all people.

Thank you for begrudging me this last of soapboxes, and as always, think more, believe less.