The Incas were a brilliant and vast empire. They had control over substantial amounts of land, flourished without Western conventions, and remained this way for long time. So it is no surprise that the United States, which fancies itself to be a great empire, wants to achieve this same greatness.

The Incas were a brilliant and vast empire. They had control over substantial amounts of land, flourished without Western conventions, and remained this way for long time. So it is no surprise that the United States, which fancies itself to be a great empire, wants to achieve this same greatness.

After much speculation over the prospect of world domination, the U.S. has finally come to the conclusion that the best strategy in gaining supreme power over the world is through control of production (as well as the mass consumption) of something so powerful, so beneficial, and so tasty, that we are all almost guaranteed to be invincible by the time we finish dinner. I am of course referring to quinoa.

There is, however, a hitch in this plan. It is hard to achieve world domination when the key to this success cannot even be grown on your own land. The United States was projected to consume 68 million pounds of quinoa in 2013. But very little of this gross consumption was of domestically grown quinoa.

One of the only places in the U.S. that has had any luck in growing this grain is the Colorado mountains. Colorado, which is experienced in the growing of all kinds of things, has been involved in the production of quinoa since the 1980s.

However, the production of this grain is unpredictable and therefore unreliable. Although some of the quinoa production in the world comes from places like Colorado or Canada, the best grain is still found in countries such as Peru and Bolivia, which is not at all conducive to United States’ supreme power ploy. Many supporters of world domination have been working on a plan to get around this small hindrance.

Quinoa is a very difficult grain to grow. The countries that have had the most success growing it are countries in South America that have a very specific type of climate; in fact, many of these countries have trouble growing little else. But the demand for quinoa is too high. Currently, there are specialists from all over the world working to develop different types of quinoa that can grow in a plethora of climates, including coastal climates, which are abundant in the United States.

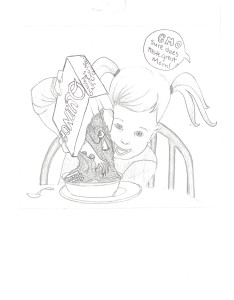

However, what will this do to the health benefits of the grain? It is a well-known fact among health nuts that genetically modified organisms (GMOs) are not as good for you as the food that can be grown completely naturally; there is even great suspicion that GMO foods can have detrimental effects on the body and mind of those who eat them.

So by genetically altering quinoa in order to increase production, who’s to say that the grain might not lose the vital health benefits that make quinoa a super-food, and that ensure the clandestine rise to power of the United States?

But aside from the mutant quinoa that is threatening our future pantries, grocery stores, and dark agendas, there is another issue at large. By all rights, the people of Bolivia and Peru should have the most access to quinoa, as they grow it and have been consuming it for thousands of years. However, due to the world’s gluttonous ingestion of this nutritious grain, the people of these countries are suddenly excluded from quinoa, which has been a staple in their diets for as long as they can remember.

Although most corporations around the world largely justify this through the increasing income per capita and standard of living of previously impoverished farmers, this may not be a good thing. Even for the advancing of world domination.

What happens when the high demands and production for quinoa uses up the land, stripping nutrients and making it impossible to get a good crop from the fields of Bolivia or Peru? Because there comes a point when, if the land is not properly cared for, or if too many modern agricultural techniques are implemented, the soil becomes useless.

It has happened countless times over centuries, when the natural or careful agriculture of a cultivated land spins out of control, over-production ensues, and the land is ruined for a great amount of time, if not forever (tobacco industry, anyone?).

Due to the world having such high expectations for production in South America, it is plausible to think that at some point the land will be over-cultivated. If this happens, and the land becomes useless, the high standard of living at this time will make no difference to the Bolivian farmers who will again be struggling to eat in 20 years. At that point in time, they won’t even be able to afford the genetically modified quinoa that will surely replace the quality product that currently inhabits our shelves and restaurants.

But what does this mean for the U.S.? If all of the quality, naturally-grown grain can no longer be grown, if the land is used up, and if the quinoa in our grocery stores is replaced by mutated, monster quinoa, then how are our plans to take over the world to succeed?

Maybe we should just bide our time and eat our quinoa, while it still contains magical properties, and await the day, not far into the future, when we will need our strength to rule supremely.