Staff Writer- Bao Vu

Anna Brandt

Well, it’s been quite a while since the last time I sat down to write a real article. If you all remember, last semester, I wrote an article about tea and made a promise about part two. It’s time to fulfill that promise.

Tea has long been a beloved beverage. Originating in China, over thousands of years, it has transcended borders and is now present everywhere. The interesting thing is, even though it’s the same tea leaf, every culture has its own unique way to enjoy it.

Japan

Many Gusties might be very familiar with the Matcha Latte at The Courtyard or STEAMery, but Matcha in Japanese culture is a different story. And actually, the term “Japanese tea ceremony” does not exist in the Japanese language. In Japanese, the term is Sadō or Chadō, which, literally translated, means “tea way” and places the emphasis on the latter word, Tao (道).

The spirit of the Japanese tea ceremony is a synthesis of philosophy and art, based on four principles: harmony (和, wa), respect (敬, kei), purity (清, sei), and tranquility (寂, jaku). Among these, “wa” is the harmony between people and nature, between the guest and the tea room, and the utensils. “Kei” is recognizing the importance of every object used; it shows the respect and gratitude between host and guest. It also expresses gratitude toward life and promotes a humble lifestyle that sets the ego aside. “Sei” is the purity and cleanliness, a cleansing of both tools and people. “Jaku” is the highest state of a serene soul, a mind as still as water.

Each cup of tea is not just a beverage, but a transmission of relaxation, expressing the harmony between mind and spirit, between the smallness of humanity and the vastness of nature.

Morocco

Moroccans like mint tea, considering it a ceremonial drink that expresses hospitality. They drink it at all times and on all occasions: when signing contracts, welcoming guests, after a meal, or simply to quench thirst. Whether rich or poor, even farmers or mountain dwellers will offer you a glass of mint tea.

Traditionally, a guest is invited to three servings of tea, each with a different nuance of flavor. The Berbers in Morocco have a proverb: “The first cup is as gentle as life, the second is as strong as love, and the third is as bitter as death.” After the third cup, the ritual is considered complete—a subtle Moroccan way of showing deep appreciation for the guest.

The special flavor of this tea always gives visitors in Morocco a sense of gentleness and freshness, and maybe somewhat, warmth.This is not just the flavor of tea, but also one that carries a hint of mystical allure, a sweet sensation clinging to the throat. The land of “Arabian Nights” has captivated many with its mystical tales, its Silk Road history, and now, its mint tea filled with hospitality.

England

Thinking of England is thinking of afternoon tea—a signature way the British enjoy tea, which has become a symbol of elegance and refinement. Starting from the simple need of an aristocrat, afternoon tea gradually evolved into an important social ritual, reflecting the British way of life and culture.

Traditional afternoon tea is often served with sandwiches, scones with jam and clotted cream, and various pastries. About 98% of the tea served is black tea, but even within that, there is a great variety. If English Breakfast tea gives a feeling of light crispness, Assam tea, with its hint of malt, makes one feel utterly cozy. Earl Grey tea, with its blend of citrus scent, offers an intensely profound experience for the senses.

We should also take a look at the decor. The aristocracy of old elevated afternoon tea culture to a “ritual.” They hunted for exquisite, high-end porcelain tea sets, bought beautiful fabric with luxurious patterns for tablecloths. Even the cake stand received focus, simplified into a beautiful three-tiered tray.

If the Eastern-style Tea Ceremony has a vibe of subtlety and mystery with its myriad detailed, meticulous rituals elevated to philosophy, then British afternoon tea gives me the feeling of nobility and elegance, like a dignified lady.

United States

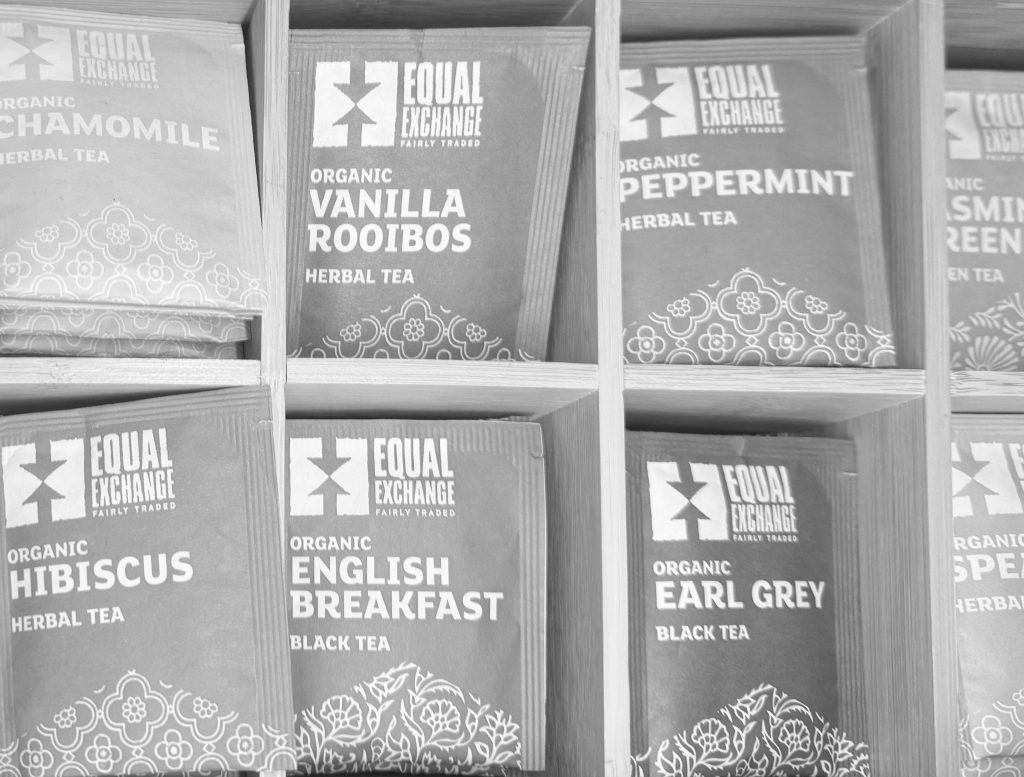

Unlike some of the more elaborate tea practices I just described, in the U.S., most people use tea bags.

I often tell my mom, American culture demands that everything be fast. They have fast food, and they also have “fast tea.” No need for a teapot, no need to strain leaves, no need for elaborate brewing techniques, they just need a pull of a string and a few minutes of waiting. And then, you have a cup of tea. This convenience fits perfectly with the fast-paced rhythm of American culture. The tea bag has, in a way, “democratized” the enjoyment of tea.

Unlike many countries that prefer the pure, bitter-astringent taste of tea, Americans usually like their tea a bit sweet. Tea often comes pre-sweetened or is mixed with syrups and fruits.

So, as we can see, the tiny tea leaf can carry on its back an entire worldview, a distinctive culture. It’s like a mirror reflecting the soul of each nation.

Writing these words, I suddenly realize that the world around us is sometimes too noisy and hurried to truly see and understand one another. We easily judge a strange flavor, a different design, or a new person, simply because they aren’t what we are used to.

We label them as foreign, as “other”.

But the story of the tea leaves from all over the world gives me a different kind of faith. It proves that beauty lies in diversity, and that human connection is nurtured through curiosity, respect, and sharing. It reminds us that before being Japanese, Moroccan, English, or American, we are first and foremost human beings who know how to offer warmth and accept differences with an open heart.

Perhaps, instead of being hesitant, we should learn to savor life the way people savor tea: slowly, sincerely, and by treasuring the unique flavors that each soul, each culture brings. That is the most universal, and also the most beautiful, “Way of Tea.”