Chances are you have been hazed. Whether or not you realize that you have been hazed is another issue entirely.

The National Collaborative for Hazing Research and Prevention, an organization led by a pair of researchers from the University of Maine, says that 55 percent of students involved in any sort of team or organization have been hazed. At the same time, however, 90 percent of these students did not think they had been hazed. Clearly, there is a semantic disconnect between these researchers and their subjects.

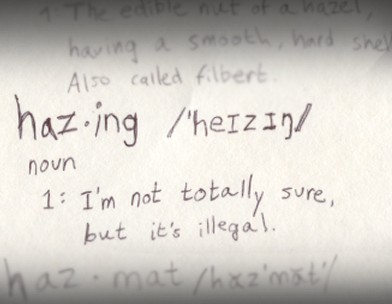

According to the Collaborative, hazing can be defined as “any activity expected of someone joining or participating in a group that humiliates, degrades, abuses or endangers them, regardless of a person’s willingness to participate.” With such a vague, blanket definition, it’s no wonder that the issue lacks clarity.

Nonetheless, one facet seems to have been unanimously agreed upon by academia, and that is that hazing is bad and should be eliminated from campuses nationwide. Calling for this and doing this, however, are two entirely different things.

Most campuses include “zero tolerance” for hazing in their regulations, but they don’t bother with actual preventative measures. Considering the aforementioned statistics, this is effectively a “don’t ask, don’t tell” scenario.

So should the issue be pursued more aggressively? A case study at Dartmouth demonstrates what might come of attempting to ask and tell.

Midway through his initiation into a powerhouse fraternity at this Ivy League school, Andrew Lohse decided fraternity life was not for him. Furthermore, he felt the men who were hazing him, and who ultimately ostracized him, should be held accountable for their actions. In an act unheard of in Dartmouth’s infamously closed-mouthed community, Lohse approached both the press and the school’s administration with information detailing the fraternity’s illegal initiation process. He even went as far as helping orchestrate an unsuccessful police sting to bust the hazing in progress.

Ultimately, his attempts failed on all fronts. The police discovered and confronted his ex-pledge brothers, but could prove nothing other than that they enjoyed drinking and singing. The school’s administration didn’t budge. Having attempted to confront the issue once before, they were met with opposition from Greek alumni who held enough political and financial power to supersede the school’s president. After all this, Lohse himself was brought up on criminal charges for being the only one to openly admit that he broke the law.

Lohse’s case illustrates several key points about the hazing problem. First, there is no clear line between initiation and hazing. Additionally, an attempt to martyr a single organization that promotes hazing only leads to an attack on a single organization, and not on the indefinable institution of hazing itself.

The National Collaboration for Hazing Research and Prevention identifies sleep deprivation as a typical sign of hazing. If this is true, then half the college professors in the nation are criminals. Defining “hazing” is difficult, but that does not mean that we cannot and should not fight it.

Perhaps it’s a noble mission, but scapegoating participants, like Lohse, is more brutal than any form of initiation I’ve ever heard of.