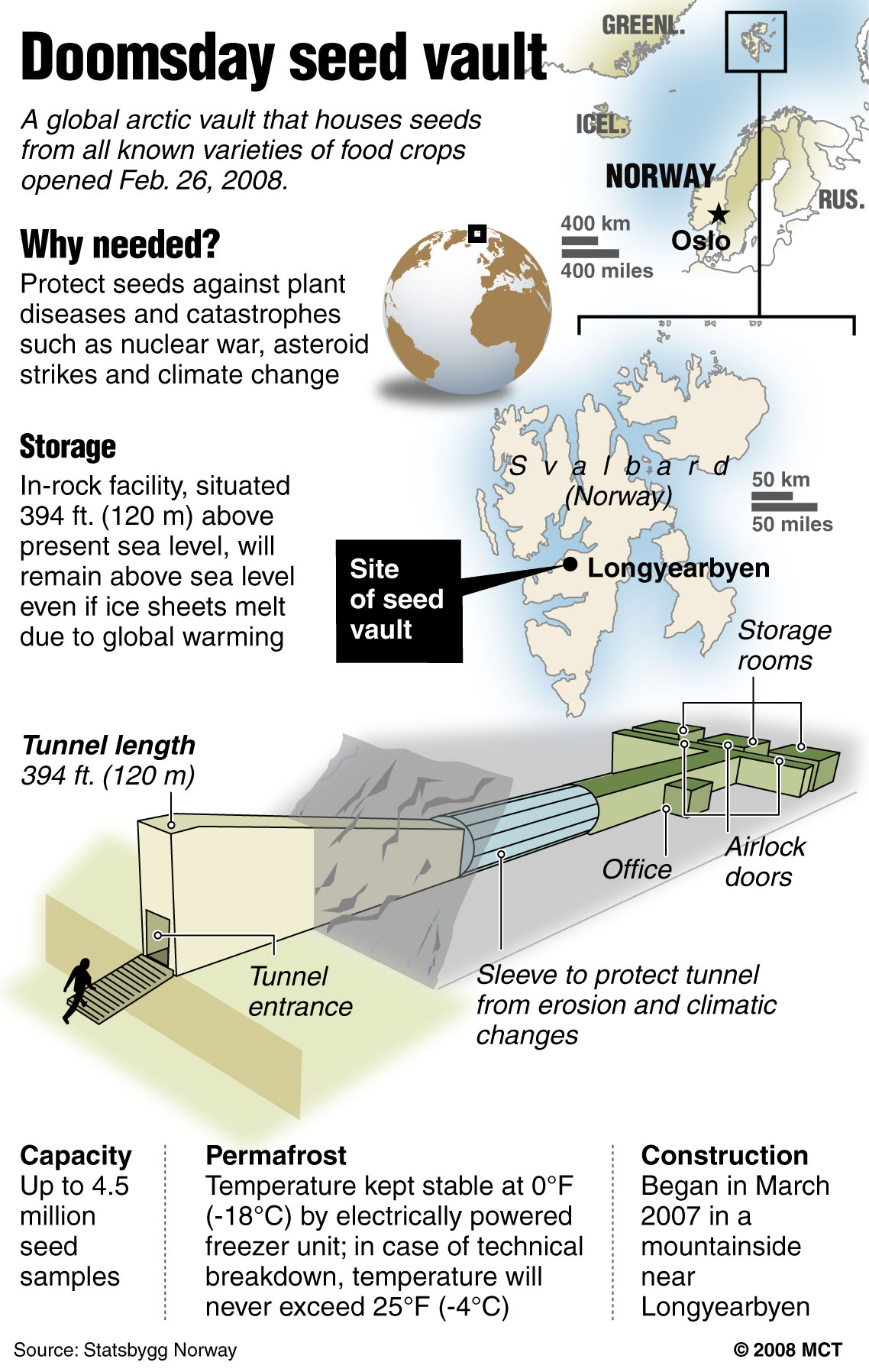

A sci-fi movie set in an apocalyptic future couldn’t have created a better story. In the frigid Arctic region of Norway called Svalbard, scientists are safeguarding humanity from destruction. Into a mountain of solid sandstone they have carved a giant underground vault with walls of steel-reinforced concrete one meter thick, dual blast-proof doors, state-of-the-art security systems and the capacity to house millions. Millions of seeds, that is.

The Svalbard Global Seed Vault was built upon the belief that, in the event of a global catastrophe, the loss of plant life that may result could have dire, if not fatal, consequences for the human race. Thus, scientists have begun storing the seeds of the world’s most valuable plants in this massive vault beneath thick layers of permafrost in order to prevent their extinction. It’s a sort of insurance policy on our planet’s biodiversity.

The seed vault will be a precious resource in the event of a sudden disaster such as nuclear war, famine, an asteroid or bioterrorism, but the cumulative effects of human environmental manipulation have the potential to be equally, if not more, catastrophic. Contemporary issues such as global warming and rainforest destruction have certainly demonstrated the fragile nature of biodiversity, but these are not the main culprits. It is centuries upon centuries of human agriculture, from the first seeds planted by early humans in the Fertile Crescent to the genetically-modified corn that blankets the Midwest, that have created a documented mass extinction of much of the world’s plant life.

The seed vault will be a precious resource in the event of a sudden disaster such as nuclear war, famine, an asteroid or bioterrorism, but the cumulative effects of human environmental manipulation have the potential to be equally, if not more, catastrophic. Contemporary issues such as global warming and rainforest destruction have certainly demonstrated the fragile nature of biodiversity, but these are not the main culprits. It is centuries upon centuries of human agriculture, from the first seeds planted by early humans in the Fertile Crescent to the genetically-modified corn that blankets the Midwest, that have created a documented mass extinction of much of the world’s plant life.

Therefore, the Svalbard Global Seed Vault is one application of technology to nature that I support. Biodiversity is essential to human survival. It is, for example, why we evolved the ability to absorb nutrition from so many plants: early humans had access to a multitude of food sources so their bodies made the best use of them. It took us millions of years to develop these capabilities, but only a few thousand years to dramatically limit our diets to a handful of grains, a few vegetables and three or four meat sources. On top of it all, it has only taken about one hundred years to add a whole flock of synthetic ingredients to our menu. Decreasing biodiversity has created a global diet that just doesn’t suit our biological needs. Especially in the developed world, increasing rates of obesity, heart disease, diabetes and cancer point to our inability to evolve fast enough to handle this diet.

Furthermore, these very diseases, along with many others, may have cures lying undiscovered in the plant life we routinely destroy. It is no secret that nature has given us a wealth of medicinal plants, but more importantly, it has given us opportunities to isolate medicinal compounds and synthesize them in laboratories to create life-saving drugs. This might be the most devastating loss we suffer as biodiversity declines. As medicinal science progresses at exponential rates, we are losing the very tools that we are finally understanding how to use.

So just how much has biodiversity declined during human history? Seventy percent of biologists say we are in the midst of a “sixth extinction,” following five other massive extinctions that have occurred every fifty million years or so, according to the American Museum of Natural History. All of these previous extinctions were caused by climate changes brought on by forces such as asteroids, ice ages or volcanic explosions, but this extinction would be the first to be caused by a species. Most scientists say this extinction event is the fastest one ever, and if it continues at its current rate, half of all living species could disappear in one hundred years.

The Svalbard Global Seed Bank can’t preserve every plant on the planet—humans have only identified a mere fraction of them—but the idea of preservation in the face of destruction is a noble one. While I can’t get behind using technology for purposes of “climate engineering,” such as injecting reflective particles into the atmosphere to bounce increasingly harmful UV rays back into space, technology is our most valuable tool in combating climate change and, as the seed vault demonstrates, in preserving what we have left. It’s an intelligent use of the key ingredient that has been missing from our historical manipulation of the environment thus far: foresight.

Asteroids, famine and nuclear war are all certainly possible, but devastating losses in biodiversity from human impact seem imminent, if not already in existence—and I’m glad somebody is saving up, just in case.

Photo courtesy of: MCT Campus